by Ruiping Luo, Alberta Wilderness Association

Indigenous peoples and supporters from across North America and beyond gathered to commemorate and sign the Buffalo Treaty. Photo: Ruiping Luo

When the Buffalo Treaty was first signed in 2014, I wonder if anyone understood just how far the agreement would reach. Ten years later, the Treaty has been ratified by nations from across North America and supported by many more individuals and organizations; the extent of this impact was evident at the 10th anniversary celebration, where hundreds gathered to commemorate the event.

The warm September air, the leaves just starting to turn golden, was a perfect time to appreciate the prairies, once home to millions of bison (buffalo). Wind rushed past rustling grasses and across rolling hills, whistling over exposed cliffs and teasing wisps of clouds in a vivid blue sky. Listening carefully, I could just hear the chirps of songbirds preparing for the winter, and up on the ledge, a red fox, perhaps also looking for birds, slunk among grey rocks encrusted with lichen.

Come closer, we were told during the event, sitting beneath the arbor on Blackfoot territory, come sit, come touch the earth. Because this gathering was not only about the Treaty, nor the return of the bison, but about the spiritual and cultural connections they embodied.

The Buffalo Treaty

On September 24, 2014, eight Indigenous nations from both Canada and the United States gathered together on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana to sign the Buffalo Treaty. It was the first time in over a century that an international Treaty had been signed between sovereign Indigenous nations without involving the countries’ respective governments.

The Treaty is described as “A Treaty of Cooperation, Renewal and Restoration.” It is an agreement to welcome bison back to North America, but also to acknowledge the cultural, spiritual and material connections of First Nations to these animals, and to revitalize these relationships and these lands for future generations. Since the Treaty was signed, several more nations have added their support. Many of the signatory nations have accepted bison back on to their lands, so that bison can once more be seen roaming parts of the continent.

Each year, a gathering is held in celebration of the Buffalo Treaty, where signatories and supporters convene, continuing dialogues on buffalo. This year, on the 10th anniversary of the first Treaty signing, over 50 nations and 1700 people attended, coming together to renew relationships and endorse the return of bison.

Opening ceremonies

I reached Lethbridge just as the first hints of pink crept into the sky. Between Calgary and Lethbridge, there had been a brief detour to Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, one of several sites where tours had been organized for the Buffalo Treaty guests. Along with Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, a UNESCO World Heritage Site speaking to the traditional buffalo hunts, visitors were invited to Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park (Áísínai’pi), a sacred site where carvings and paintings made by the First Nations inhabitants can still be seen. Events also took place at Blackfoot Crossing, the historical site where Treaty 7 was signed, and at the bison paddock in Waterton Lakes National Park, showcasing just a few of the connections Indigenous peoples have to Alberta.

The theme of this year’s gathering was renewal. It was about continuing and building on the work that had already been done, and it was about looking to the future. It was also about legacy, about the knowledge, traditions and the world that would be left to the children. It was with this theme that Dr. Leroy Little Bear – one of several speakers who opened the event – asked for nations to renew their commitment to the Buffalo Treaty.

Red Crow Community College, where the first day of the event took place, was bursting with activity. In the atrium, lines of people waited to register and to pick up information on the event. To the right, booths had been set up, offering cloth, jewelry, arts and more. Knots of people formed, as old friends and those who had only met online had stopped to chat.

Beyond them, in the recently completed gymnasium, the presentations were beginning. Over the next few hours, we heard from key players in the Buffalo Treaty, representatives from various nations, and individuals speaking to their experiences with bison. Stories and songs were shared. The speakers talked about their relationships with bison, about rediscovering their culture and about wisdom passed down from their elders. They talked also about resiliency, about surviving abuse and trauma and retaining their identity. They spoke of keeping their culture alive, rebuilding the connections they lost and about thinking of future generations.

Mostly, the speakers stressed that buffalo could not be separated from their ceremonies, traditions, cultures and beliefs.

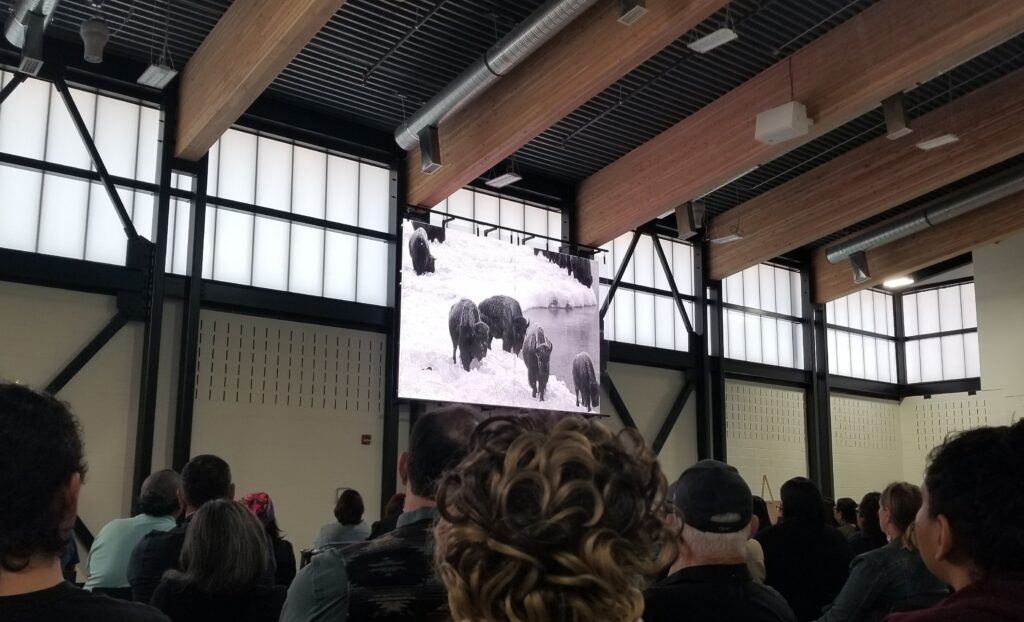

Following the theme, two documentary films were included in the schedule that explored Indigenous relationships to buffalo. The first, Singing Back the Buffalo by Cree filmmaker Dr. Tasha Hubbard, focuses on the impact of bison and their return through an Indigenous lens. The second, Iniskim – Return of the Buffalo, was a somewhat lighter story about puppetry and becoming buffalo.

Singing Back the Buffalo, a documentary about the Buffalo Treaty and the return of the bison herds, was screened. Photo: Ruiping Luo

We had returned to Lethbridge for the last film, and as the credits rolled, the drumming and singing started. We followed the music through the polished corridors of the University of Lethbridge campus and outside, where, glowing brightly, we found the buffalo. The lantern puppets shone brightly against the night sky, prancing around the grassy field and lighting up the ring of human dancers that had assembled around them. It was an extraordinary experience to end the night on.

During the celebrations, we danced around lantern puppets shaped like bison, which were used to tell the stories of the buffalo. Photo: Ruiping Luo

Buffalo Dialogues

We reconvened in Red Crow Park, under a clear blue sky. Outside the arbor – a large open area surrounded by seats and shaded by a circular wooden frame – large tipis had already been set up in preparation for the buffalo dialogues.

The Buffalo Dialogues have been occurring since before the Treaty was first signed. These are places for people to share knowledge and stories, and to have discussions. Participants were asked to be respectful, to leave their walls outside, and to speak freely. This year, smaller groups gathered in various tipis, each focusing on a different part of the Buffalo Treaty.

Inside one tipi, where the topic revolved around conservation, a ring of chairs had been set up, and a smaller ring of blankets provided additional seats for visitors. Both rings soon filled with people. We began with a smudging ceremony, to allow the smoke to cleanse our thoughts and speech, we were told. Then a dialogue guide, responsible for directing the conversation, introduced us to the talking stone; only the holder of the talking stone – in this case, appropriately, a carved bison – was permitted to speak.

The point of this conversation, we were told, was not to have an agenda. It was not to leave with clear action items and next steps. The point of the conversation was, simply, to listen.

Many different perspectives were shared in the following hours. We spoke of the culture and the history of the animal, about the separation in science between people and nature, about the need to integrate culture. We heard stories of their return and the changes in how bison are treated. There remained divides, between Indigenous and western science, between the management of bison as wild or domestic livestock, in the safe introduction of the species, and in what conservation means to different people. In both the discussion and in conservation, the categorization of people and ideas remained a barrier, and at times, the dialogue became more difficult, touching on sensitive topics related to history or deeply held beliefs. Although some of these disagreements were acknowledged, they were not resolved. Still, throughout the dialogue, there was general optimism for the future of bison conservation in North America.

Signing the Treaty

On the last day of celebrations, under the warm morning light, the signing of the Buffalo Treaty commenced. Representatives from 30 Indigenous nations from across North America had come to affirm or re-affirm their commitment, many presenting speeches and bearing gifts, rallying around the principles of the Buffalo Treaty. In their wake were others, that pledged their support towards the Treaty and bison reintroductions. This year, AWA joined the supporters of the Buffalo Treaty.

The 10th Anniversary of the Buffalo Treaty was a renewal, of the Treaty and of the spirit and inspiration that has already returned hundreds of buffalo to North America. During these days of celebration, alliances were formed and strengthened, experiences shared, and a commitment to restoring bison restated. These relationships and understandings will be vital to face the challenges still ahead, as we continue to return this resilient species to their place on the lands of North America.

Alberta Wilderness Association representative Ruiping Luo signing the Buffalo Treaty. Photo: Marie-Eve Marchand